Introduction:

You may be wondering, oh boy, what’s he up to now? Why architecture? Let me explain…In 2011, I was transferred from the Fine Arts Library to Special Collections at the University of Arizona Libraries. I have done a variety of work while there, including managing the department’s exhibits and events programming and curating exhibits. While that work was extremely rewarding and I had a great time creating some fun exhibits and programs, in 2019, my duties changed. I now serve as curator for the Library’s performing arts and architectural collections and I manage reference service for the department. My passion for local history and love of local architecture help fuel my desire to learn all I can about the topic, particularly about the various architects who have worked in Tucson and Arizona. My intention with this posting is to introduce folks to the collections housed in Special Collections and to promote use of these collections among students, scholars and the general public.

THE ARIZONA ARCHITECTURAL ARCHIVES

The University of Arizona has had an architecture degree program in place since at least the 1960s and for a time, the School of Architecture had its own departmental library. However, over the years, because of decreased state funding, budgets for things like departmental libraries have shrunk to the point that collections and services have been consolidated where possible and facilities such as the Architecture Library have been closed. The College of Architecture’s library closed in the mid-2000s and the bulk of its collections were absorbed by the University Libraries.

The majority of the architecture-related holdings housed in Special Collections at the University of Arizona come from a collection called the “Arizona Architectural Archives”. This collection was started in 1976 at the College of Architecture Library and its purpose was “to provide documentation of the architecturally significant structures in Arizona, and of the architects and builders who have played a significant role in their field in the state”.

(Gresham, 1982. “Collections of Drawings and other records related to the buildings and the practice of architecture in Arizona”. Arizona Architectural Archives).

Initially, the collection included works by the following architects:

Place and Place (1918-1967) 88 projects are represented, most of which were completed before 1955. Roy Place is credited with creating the “style” of the UA campus. Many of the early campus structures were built by his firm, which at the time was called Lyman and Place. John B. Lyman, who had moved to Tucson in 1917 partnered with Roy Place to build the Mines and Engineering Building, the Steward Observatory, the University Library (now the Arizona State Museum) and the Memorial Fountain, among other structures on the UA campus. After Lyman left the firm in 1924, Roy Place continued building on campus and his son joined him as a partner in 1940. Place also designed the Pima County Courthouse, Mansfeld Jr. High, the Arizona School for the Deaf and Blind, and the Pioneer Hotel. He died in 1950 and his son Lew continued the work of the firm until 1976. The collection of drawings by Roy Place and his associates was donated by Lew Place in 1976.

Henry O. Jaastad A Norwegian born in 1872, Jaastad immigrated to the US in 1886. He moved to Tucson in 1902 and worked as a cabinet maker and carpenter. He also studied electrical engineering at the University of Arizona. He became an architect in 1908 and designed mainly residential buildings. He was a member of the Tucson City Council and also mayor from 1933 to 1947. He expanded his architectural practice over the years and built churches, schools and hospital buildings as well as other buildings for public use. He died in 1965 at the age of 93. Public buildings built by Jaastad include Roskruge Jr. High, Drachmann School, the Southern Arizona Bank, and the YWCA buildings. Nearly 300 projects were completed. Annie Graham Rockfellow worked for him as the lead designer for the firm but never received proper credit for her work.

D. Burr DuBois 1901-1979. DuBois graduated from the School of Architecture at the University of Michigan and moved to Tucson in 1926. He worked for a number of different architects including Henry O. Jaastad and James MacMillan, but always did his own work as well. He built the Himmel branch of the Tucson Public Library and was responsible for several additons to various University of Arizona buildings, including the Student Union Memorial building. His collection includes 570 drawings and five boxes of records and cover the time period, 1937-1968.

Russell Hastings 1909-1979. Hastings moved to Tucson in 1931 to study archaeology but didn’t stay long, but he returned in 1939. By 1950 he had become a registered architect with the State of Arizona and he designed residential buildings, schools and other dwellings. These include the Adair Funeral Home, the Immaculate Heart Academy, Magee Jr. High, two A & W restaurants and many residential dwellings. The collection includes 110 projects and over 1000 drawings done between 1950-1978.

Over time, since the closing of the School of Architecture Library, the Arizona Architectural Archives collection was moved to a variety of locations. The University of Arizona Libraries acquired the bulk of the collection in 2011, although some of it now resides at the Tucson division of the Arizona Historical society. (See library_Architectural-Drawing.pdf)

While inventories of the collections that are housed in Special Collections exist, they are not yet publicly available. However, they can be searched and viewed with assistance and advance notice. You can reach me at jrdiaz@email.arizona.edu or contact Special Collecions at: askspcoll@email.arizona.edu and I or one of my colleagues will be more than happy to help you.

NEW ADDITIONS:

The following collections are available to the public, and, with the exception of the Joesler drawings noted below, have finding aids that are available in Arizona Archives Online. They include:

Judith Chafee Papers MS 606: This collection includes a variety of materials pertaining to the life and work of architect Judith Chafee. The majority of the collection are project files and architectural plans corresponding to Chafee’s award winning designs, but it also includes photographs, artwork, poetry, publications, office documents, and teaching files from Chafee’s time as an architecture professor. A brand new book about Judith Chafee, titled Powerhouse: The Life and Work of Judith Chafee, written by Kathryn McGuire and Christopher Domin, is now available. A companion exhibit is also available for viewing at the School of Architecture.

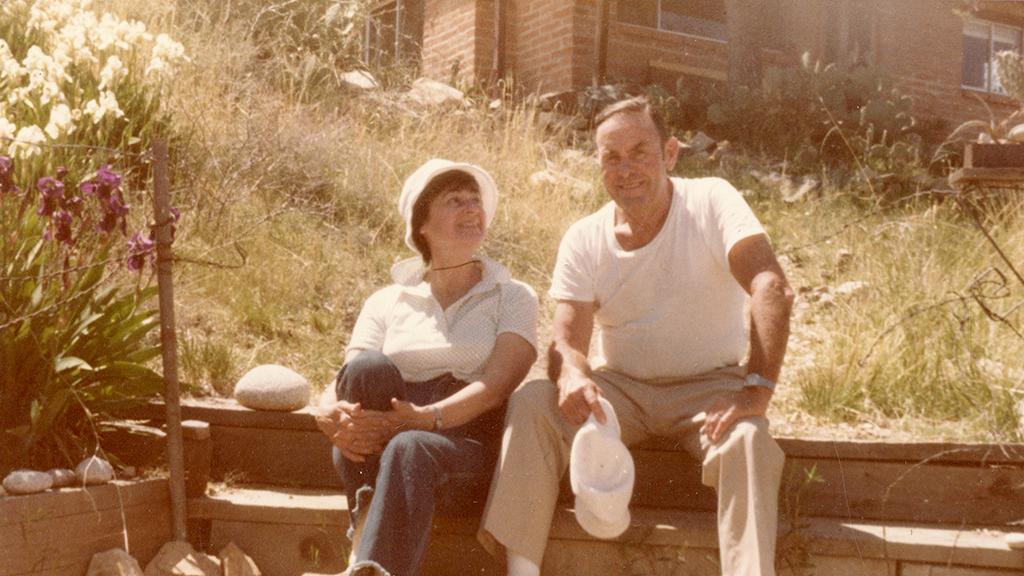

Thomas Gist papers, 1918-2000 MS 655 “This collection consists of the personal and professional papers and drawings of Tucson architect, Tom Gist (1918-2000). His unique design and building style made his homes an important part of Tucson’s Historical Districts. The bulk of the material relate to his work as an architect and include his drawings, plans, contracts, and other important information pertaining to his work. The rest of the collection stems from his personal life and contains various awards, degrees, photos, scrapbooks, and journals including his work with the Tucson National History club.” (from the finding aid)

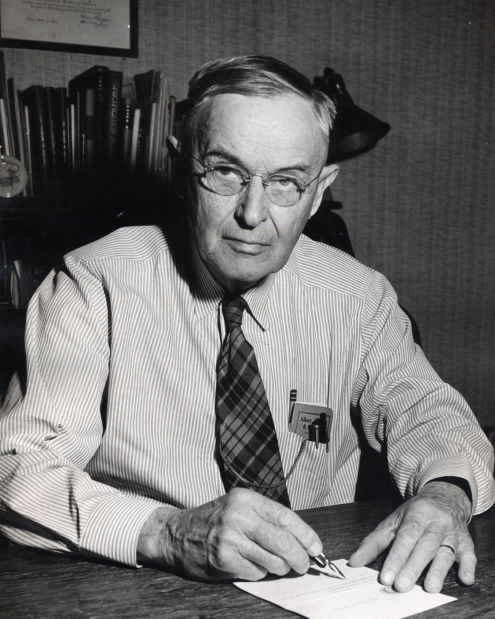

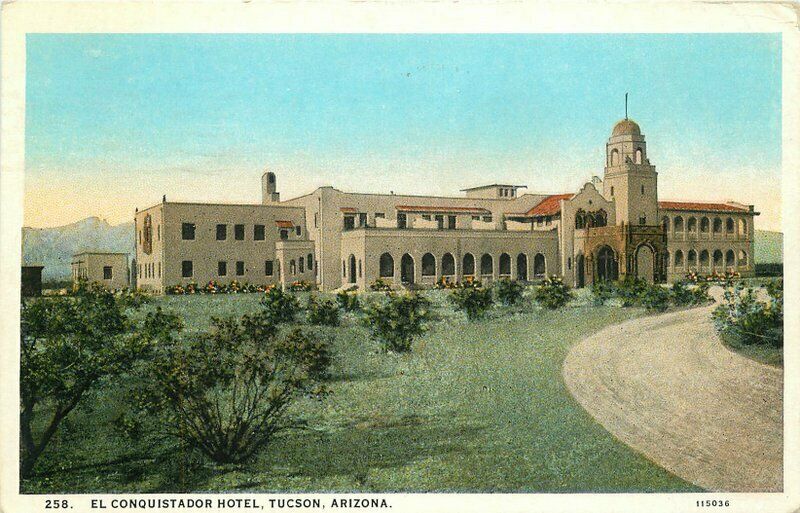

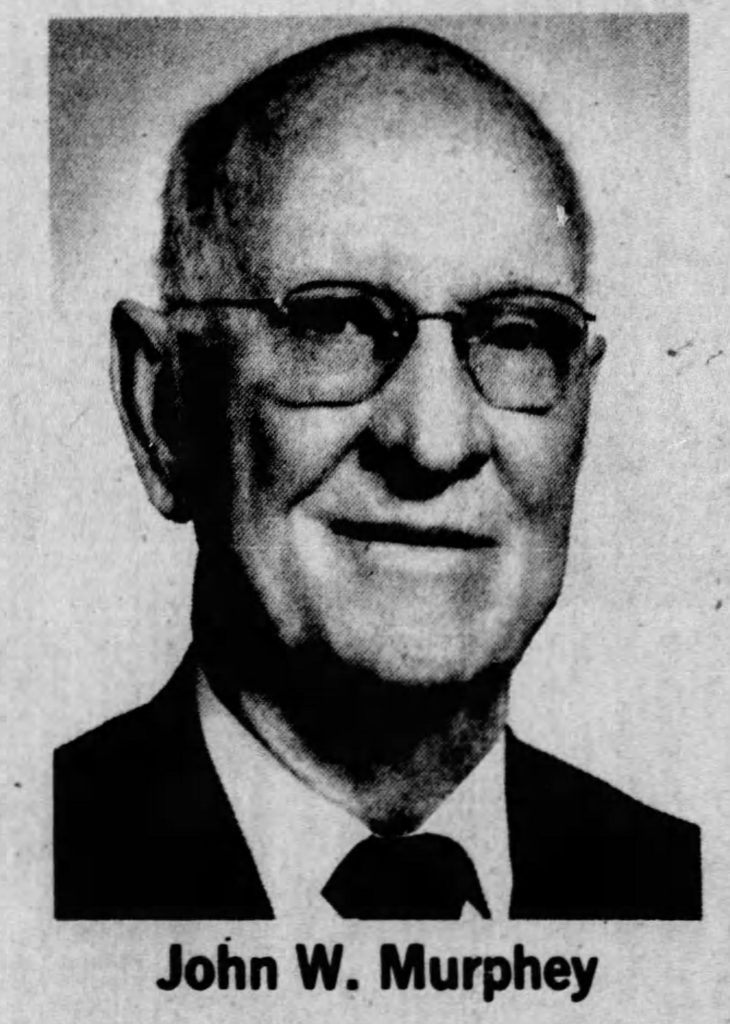

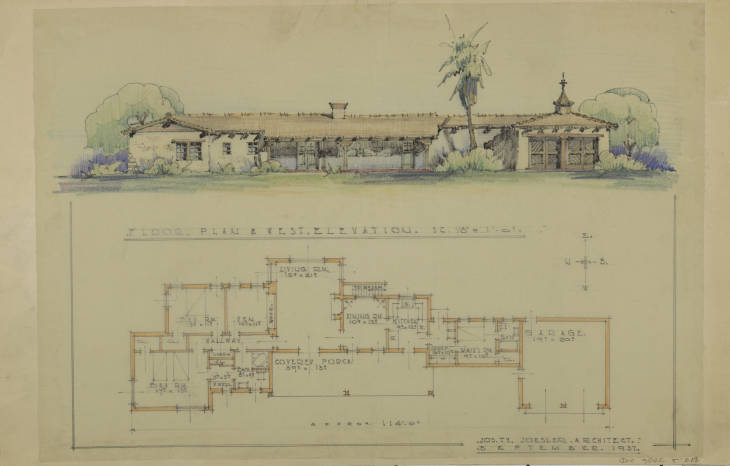

John W. Murphey records 1919-1972 (bulk 1920-1950) MS 603 Along with Leo B. Keith and Helen Geyer Murphey , his wife, John W. Murphey owned and operated a number of commercial ventures in Southern Arizona beginning in the 1920s. In 1928 the John W. Murphey and Leo B. Keith Building Company was incorporated and Josias Joesler was hired as the firm’s architect. Fourteen years later, in 1942, the company was re-organized as the Murphey and Keith partnership, at which time Josias Joesler sold his shares. Into the 1950s, Murphey and his associates constructed homes, performed renovations, sold property, and leased houses in the Tucson area. Large projects include whites-only housing developments such as the Catalina Foothills Estates and Broadway Village, commercial spaces at Broadway Village and St. Phillips Plaza, the Hacienda Del Sol hotel, and the El Conquistador hotel. After Joesler’s death in 1956, Murphey began working with architects Blanton and Cole.

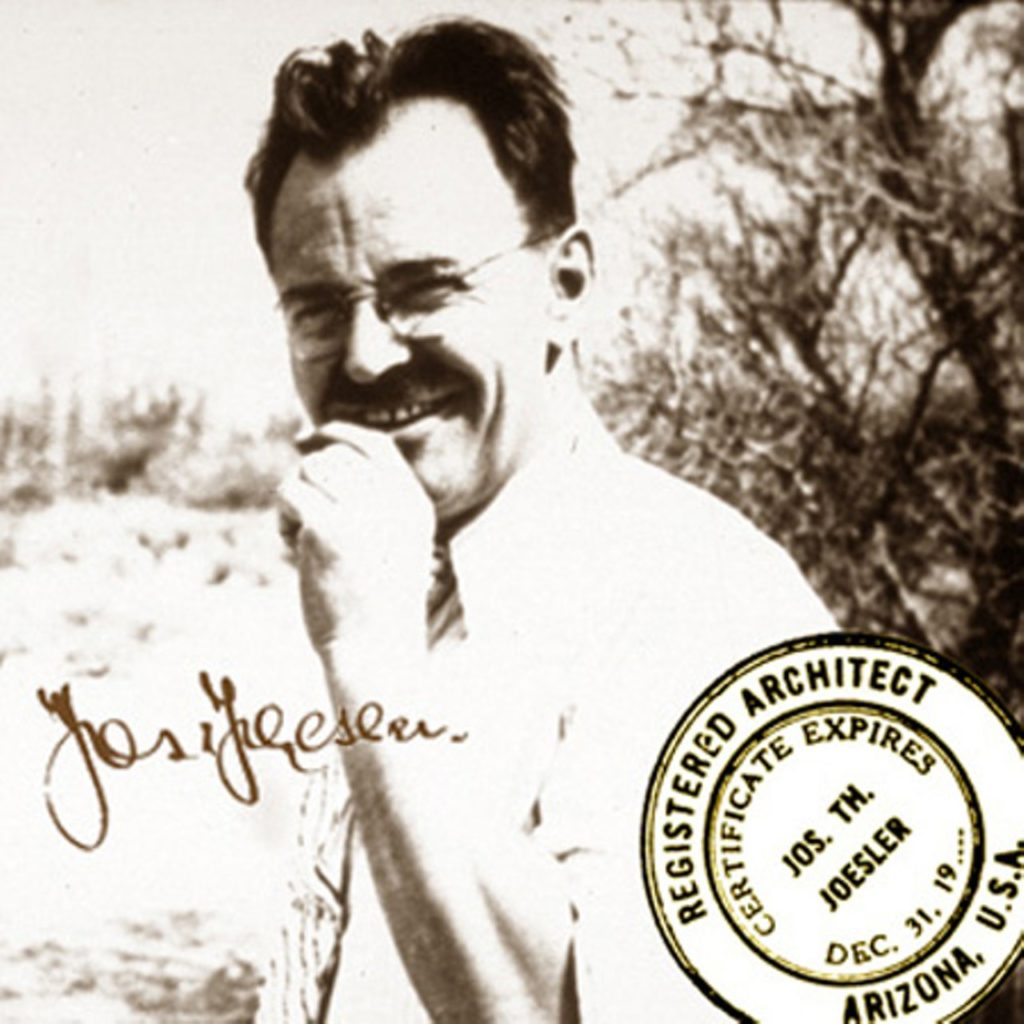

Josias Joesler: Born in Switzerland in 1895, Joesler was educated in various places throughout Europe. He moved to Los Angeles in 1926, and shortly thereafter met John and Helen Murphey. After settling in Tucson in 1927, Joesler worked with John Murphey for thirty years, until his death in 1956. Joesler designed over 400 projects, including commercial buildings, churches and residences. St. Phillips Plaza and St. Phillips in The Hills are among his many works that showcase his love for the Spanish neo-colonial style of architecture. Today, his Tucson homes are highly sought out and they command a hefty price. For more information see: Josias Joesler | Through Our Parents’ Eyes.

The Joesler Collection of Architectural Drawings is available for viewing in Special Collections. Digital versions of these drawings are also available online at: https://content.library.arizona.edu/digital/collection/Joesler

Backlog: Much of the material contained in the Library’s architectural collections has yet to be fully processed. Among these are:

- Architecture One office files

- Aros and Goldblatt office records and drawings

- Atkinson drawings

- Cain, Nelson and Wares office files and drawings

- Cole drawings

- Gourley office files and drawings

- Green, Ellery office files and drawings

- Hall drawings

- Hockings drawings

- Lockard, Kirby drawings

- Luepke, Gordon drawings

- Sakellar, Nicholas office files and drawings

- Wilde, Willam office files and drawings

- Zube office files

While the above collections constitute the bulk of our backlog, there is more material available. If you have any questions or would like to find out more about our collections, please contact me at jrdiaz@email.arizona.edu.

Work is underway to acquire a handful of additional collections, but given that architectural drawings take up a lot of space, time will tell how much more material the Library will be able to accomodate as it is running out of storage space.

If you are interested in doing research in the areas of architecture, planning or landscape architecture , see the following subject guide. You may also contact me or my colleague Rachel Castro, (castro2@email.arizona.edu ), who is the departmental liaison for the College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture at the University of Arizona Libraries.

La Adelita

La Adelita